One of the most surprising economic trends of the past few years has been how the stock market has kept climbing despite nearly a decade of constant economic, social, and (geo)political turmoil. Sometimes I wonder if it is running on little more than vibes.

To get a better grip on the situation, I decided to look at some historical data. I focused on the S&P 500, a stock market index that has been tracking 500 publicly traded companies in the United States since 1957. It is often used as a performance benchmark, and the listed stocks account for about 80% of the total market capitalization, including the likes of Apple, Nvidia, Microsoft and Alphabet (Google).

In mid-1957 the inflation-adjusted S&P 500 price was about $528, doubled to $1,125 by mid-1995, and is around $6,730 today. Of course, the American and global economies have grown a lot as well.

U.S. GDP in constant dollars rose from about $7.6 trillion in 1995 to roughly $29.1 trillion in 2024, close to a fourfold increase. Over the same period the inflation-adjusted S&P 500 level rose from about 1,125 to about 6,730, close to sixfold. However, from 1960 (at $542 billion) to the early 1990s, real GDP increased by more than ten times while the real S&P 500 rose much less. So, what gives?

Big Shifts

Of course, many things changed in the global economy after the 1960s: technological advances, regulatory shifts, and new forms of production, and the stock market has always had a clear upward trend. Nevertheless, I wanted to see whether I could pinpoint some specific years when trends shifted.

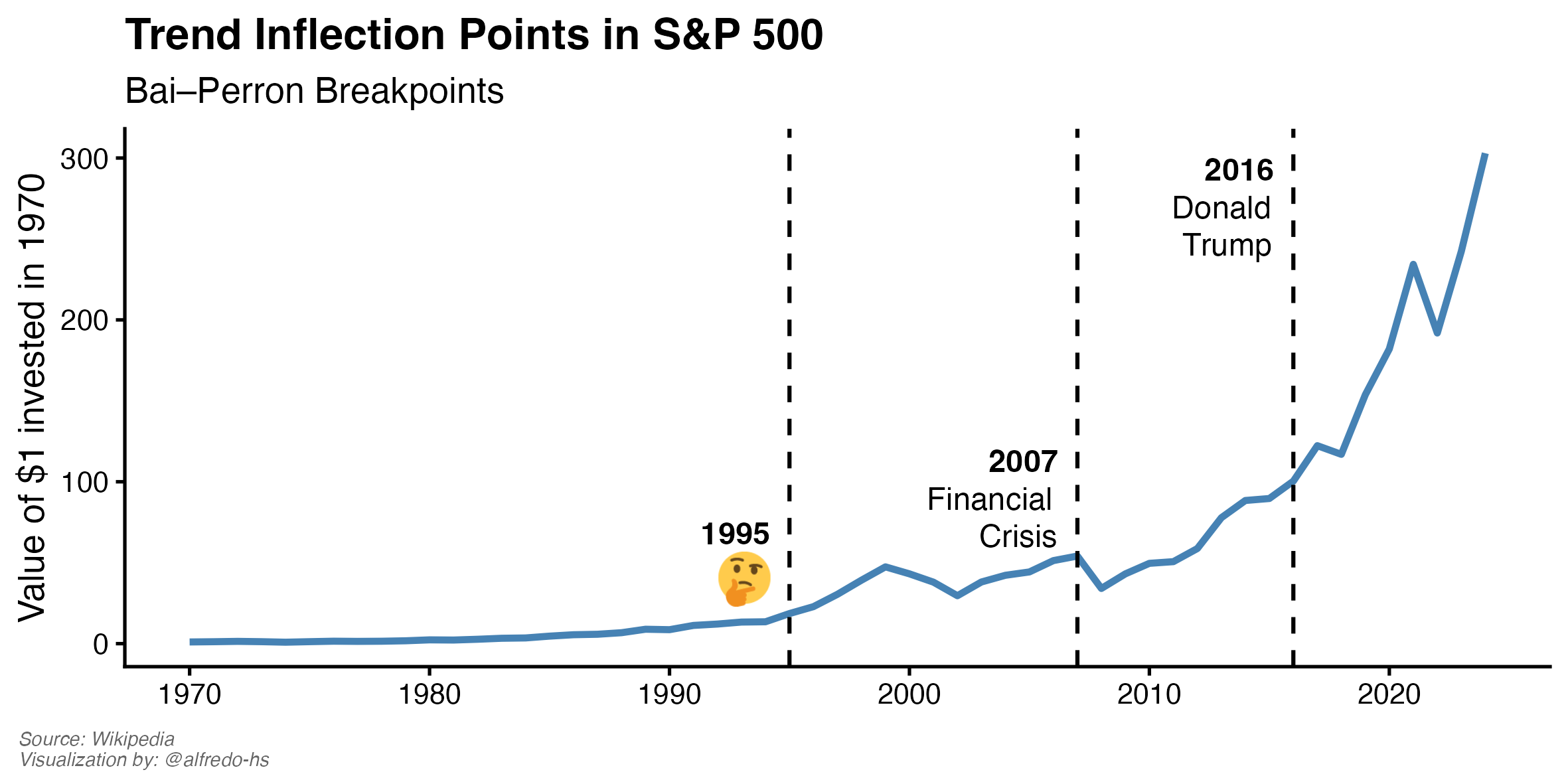

The chart above plots the value of one dollar invested in 1970 for the S&P 500 over time. The blue line rises slowly through the 1970s and 1980s, steepens in the mid-1990s, flattens around the Global Financial Crisis, then accelerates sharply after 2016. The vertical dashed lines at 1995, 2007, and 2016 are Bai–Perron structural break test estimates.

The Bai-Perron test finds moments, or breakpoints, in a time series where the linear trend changes. It searches over many possible break positions and chooses the ones that best fit the data. The Global Financial Crisis and the first Trump election help explain the 2007 and 2016 breakpoints, respectively, with a sharp drawdown after 2007 and a strong upswing after 2016.

However, something seemingly just as important changed in the mid-1990s.

Celebrity CEOs

Trying to think about a watershed moment that might explain why the algorithm selected 1995 specifically, I was reminded of a classic anthropology paper on value, the dot-com bubble, and this Substack post on the vibecession.

Anthropologist Daniel Miller (2008) documented the rise of the shareholder value discourse in the U.S. corporate culture of the 1990s. The idea that companies should focus on nothing more than returns as opposed to “social responsibility” can be traced back to Milton Friedman – to absolutely no one’s surprise – in the 1970s. Nevertheless, it was really in the mid-1990s when the value of shares became the bottom-line for large corporations and “CEOs [became] a kind of celebrity capital in the quest for shareholder value” (Miller, 2008, pg. 1125).

It was also between 1995 and 2000 when Internet companies came to dominate the stock market (though mostly the Nasdaq) resulting in a crash and the collapse of several companies such as the infamous pets.com. This huge gap between “quaint” traditional valuation factors such as profits and the value of stocks inspired Alan Greenspan to coin the term irrational exuberanceto explain this curious anomaly. After all, financial markets should be efficient, not vibes-driven.

When thinking about what moves the financial system we have been conditioned to focus almost exclusively on economic and political factors, on rational calculations about power and profit over nebulous and emotions and narratives. Yet compelling stories and charismatic CEOs seem to influence the movements of the market as much as balance sheets.

It might thus seem like feelings are now exerting an outsized or undue influence on the economy. Yet sentiments have long been acknowledged as a key part of economic thought, from Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments to John Maynard Keynes’ Animal Spirits. The quasi-doctrinaire belief that the building block of economic life is the rational homo economicus who pursues little but marginal utility and inhabits a world of general equilibrium is a relatively recent intellectual development.

Nevertheless, as economic narratives receive more attention by scholars and the general public, it is important to reflect on when character archetypes such as celebrity CEOs first entered the stage. Alas, as the Tesla tragedy has shown us, once the charisma of these protagonists peters out, the curtain also drops on their stock rallies. A rizzcession perhaps?

Causation?

So, does this mean that the rise of shareholder value culture caused the jump in the price of stocks? No. At least not that we can determine by looking at this data alone.

To make a causal argument one would need to calculate a convincing counterfactual, some way estimating how the stock market would have looked like in the absence of this new way of looking at the value of companies. It would also be necessary to consider the possible effects of other developments around that time, such as the 1993 launch of the first exchange-traded fund (ETF), which tracked the S&P 500 (SPDR) or the tax code changes of the 1990s like the lowering of top marginal capital gains tax in 1997.

It is also important to note with visual narratives such as this one that changes in the parameters of the calculations, and the assumptions of the models heavily influence the results. This is why reproducibility and transparency are so important!

In this case, I used naïve standard errors and elected to look at changes in the absolute value, not the growth rate (e.g. log prices). The full calculations as well as some robustness tests are available in this GitHub repo.

This post was originally published on Medium and can be found here.